American Friends Service Committee - Aging in Prison, 2017

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

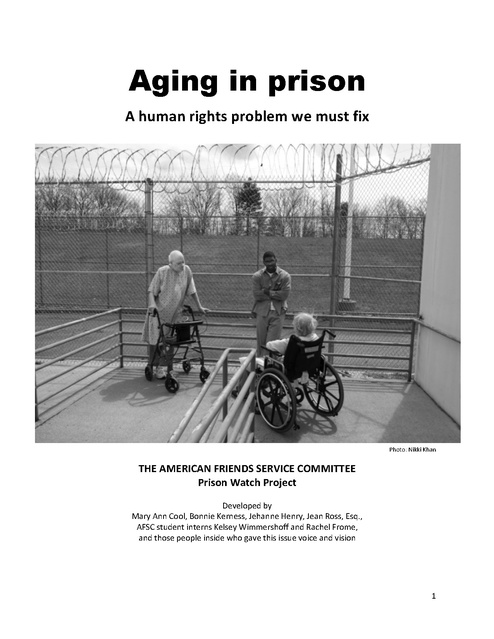

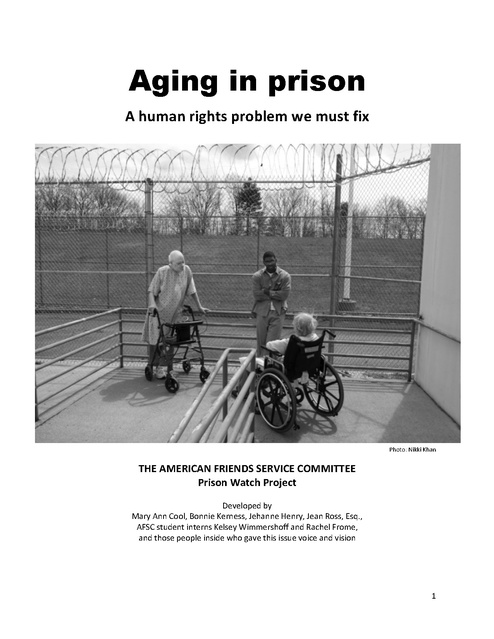

Aging in prison A human rights problem we must fix Photo: Nikki Khan THE AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Prison Watch Project Developed by Mary Ann Cool, Bonnie Kerness, Jehanne Henry, Jean Ross, Esq., AFSC student interns Kelsey Wimmershoff and Rachel Frome, and those people inside who gave this issue voice and vision 1 Table of contents 1. Overview 2. Testimonials 3. Preliminary recommendations for New Jersey 4. Acknowledgements 3 6 11 13 2 Overview The population of elderly prisoners is on the rise The number and percentage of elderly prisoners in the United States has grown dramatically in past decades. In the year 2000, prisoners age 55 and older accounted for 3 percent of the prison population. Today, they are about 16 percent of that population. Between 2007 and 2010, the number of prisoners age 65 and older increased by an alarming 63 percent, compared to a 0.7 percent increase of the overall prison population. At this rate, prisoners 55 and older will approach one-‐third of the total prison population by the year 2030.1 What accounts for this rise in the number of elderly prisoners? The rise in the number of older people in prisons does not reflect an increased crime rate among this population. Rather, the driving force for this phenomenon has been the “tough on crime” policies adopted throughout the prison system, from sentencing through parole. In recent decades, state and federal legislators have increased the lengths of sentences through mandatory minimums and three-‐ strikes laws, increased the number of crimes punished with life and life-‐without-‐parole and made some crimes ineligible for parole. Even when release becomes judicially permissible parole boards focus on long-‐past offenses without giving sufficient weight to individual and statistical evidence of decreased risk. Many states have also adopted harsh parole revocation policies, which cause more parolees to return to prison for technical violations of parole rules, not new crimes. As a result, more people are serving longer sentences; they are aging and dying in prison. What’s the situation in New Jersey? New Jersey tracks the national trends. The state has taken important steps to reduce its prison population by reducing the scope and magnitude of mandatory minimum sentences for narcotics offenses. But the Department of Corrections does not adequately address the needs of the rising proportion of older prisoners who cannot benefit from these changes. Eligibility criteria in the laws permitting the parole or release of medically compromised prisoners are narrow and strict. As a result, the New Jersey Department of Corrections reports that there were 445 more prisoners over age 55 in 2016 than in 2011.2 New Jersey’s No Early Release Act limits parole eligibility for people convicted of certain serious crimes.3 But long-‐term elderly prisoners who pass these legislatively imposed benchmarks are still likely to be denied release by a Parole Board which gives undue weight to their decades old offenses. Moreover, the Board also imposes long periods between parole hearings, leaving elderly persons to await death in prison. Equally troubling, people with serious mental illness are kept in prison rather than being paroled under commitment to mental health institutions. When these elderly ill prisoners are finally released at the end of their maximum sentences, they are returned to the community without adequate provision for mental health supervision and treatment.4 3 What is the impact of imprisonment on aging prisoners? The physical and mental health consequences of aging in prison can be devastating. The full range of ailments normally associated with aging may be accelerated or compounded, as prisoners often lack the appropriate medical care, food, socialization, and exercise facilities needed to keep aging people healthy. The psychological impact of aging in prison is also an important factor affecting prisoners' health status, since depression and other psychological effects can undermine good health.5 These factors account for a consensus that age 55 delineates the elderly population in prison.6 The impact of the conditions of confinement on New Jersey’s aging prisoners is clear: many of those interviewed reported facing difficulties in access to basic services and as a result their health was deteriorating. Many also talked about the psychological impact of long sentences. [For more details about these problems, please see the testimonials below.] Although there is a medical building for seriously ill or disabled people in one state prison, there are no special units for the many frail, sickly and poorly functioning elderly people in the rest of the system. These people are often double-‐celled with younger adults, who may either help care for them, or who place them at risk of harm. Can aging prisoners apply for “geriatric” release? Only 15 states and the District of Columbia have a process for releasing geriatric prisoners. These policies vary, but they generally involve parole, furloughs and medical or compassionate release and might include various criteria including age, amount of time served, medical condition and risk to public safety. In many states these procedures are rarely used, and specifically exclude people with violent and sex offense histories. Since prisoners over 55 are often in for long sentences, based on serious offenses, they may be less likely to qualify for these programs.7 In New Jersey, the rules are very strict for applying for medical parole, medical release and clemency. In general, prisoners have to demonstrate they have a terminal condition with less than six months to live, or have not been convicted of a serious crime. Most elderly prisoners do not qualify for this narrow condition for release. In 2015, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie vetoed a bill that would have expanded the criteria for medical release to prisoners with a permanent physical incapacity.8 Without any special provisions for "geriatric release," older prisoners are subject to general parole practices that keep many people in prison unnecessarily. What is the cost of caring for the aging prisoner population? One profound impact of an aging prison population is the enormous cost in housing and care for elderly prisoners. Aging prisoners require more medical care, making them a costlier segment of the prison population. According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, prisoners older than 55 have an average of three chronic conditions, and as many as 20 percent of them have a mental illness. Their need for medical services, including medications and devices such as walkers, wheelchairs, hearing devices and breathing aids is significant. Therefore, older prisoners are at least two to three times as expensive to imprison as younger prisoners, chiefly because of their greater medical needs.9 4 As a matter of criminal justice policy, the cost of imprisoning elderly and sick prisoners cannot be justified because they generally do not pose a risk to the outside world and are unlikely to re-‐offend. What does international human rights law say about imprisoning elderly people? While international human rights law does not preclude imprisonment of older people, the practice of doing so raises two major concerns. First, the conditions of confinement should be consistent with the requirements of human rights law. Older prisoners, like all prisoners, have the right to be treated with respect for their humanity and inherent human dignity, to be free from torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, to receive appropriate medical and mental health care, to have reasonable accommodation for their disabilities and to be provided activities and programs to support their rehabilitation.10 In New Jersey and many states across the country, conditions are clearly not adequate to deal with the infirmities that come with age. Human Rights Watch research found that in many states the rights of elderly prisoners were violated by a combination of limited resources, resistance to changes in longstanding rules and policies, lack of support from elected officials and insufficient internal attention to the unique needs of older prisons.11 Secondly, aside from the conditions of confinement, a prisoner’s sentence should not impose a disproportionately severe punishment. Yet in many cases, the length of a prisoner's sentence bears an insufficient relationship to the harm caused to others or the community. International law states that disproportionately lengthy prison sentences may violate the prohibition on cruel and inhuman punishment and can amount to arbitrary deprivation of liberty. Even if the length of the sentence were proportionate at the time of sentencing, the analysis of proportionality changes with age. When prisoners have grown old and frail or ill, the purposes of imprisonment—deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and retribution—are no longer met through continued incarceration. Older prisoners are less likely to commit additional crimes after their release than are younger prisoners; they are often incapacitated due to frailty, disability or illness; long imprisonment impedes rehabilitation; and the retributive purpose of their imprisonment could be achieved through alternatives controls, such as conditional release. 5 Testimonials Our interviews with 14 men and women, between the ages of 52 and 79 and who are currently in or were recently released from prison in New Jersey, show how the state’s prisons have failed to provide appropriate conditions for the aging population. They described a lack of appropriate medical care, diet and exercise and the trauma of being in prison for prolonged periods. OL, a 71-‐year-‐old man who has served 28 years in state prison, described the inadequate care for aging prisoners: “In prison the elderly need more care in terms of both operations and medications than the average younger prisoner. The system doesn’t want to spend the money they need to on older prisoners. So they’d get third or fourth rate drugs to treat your ailments. They’ll put off a surgery you need for years and years. […] Say a prisoner loses control of their body functions they might be in a hospital unit sitting in their waste because no one wants to change them. Nurses don’t want to deal with prisoners that way because they say it’s a dirty job. So they’ll have the prison interns do it. If it’s overnight, the prisoner will have to sit in it all night until the following day. It’s a terrible thing to go to prison but it’s worse to grow old in prison.” DG, age 54 who served 21 years, recounted how he was denied prompt treatment: “I suffer from a herniated spine and scoliosis. In 2002 I was in a prison fight on the yard where I was injured and put in the hole for a fight I did not cause. I was in the whole for two weeks the guards did let me see the medical staff after a week of the incident.” MU, a 54-‐year-‐old woman who spent ten years in state prisons, described how medical care could be used to discriminate against some prisoners. “The medical situation in prison is political. […] If a person has a medical condition to be checked on or if they have to do their annual to check on their health the process is they can use it as a form of punishment. [… ]There is a list of people and your name didn’t come up yet and you will be damn near dead before you are seen. For example, what’s happening with Mumia. We know they are using the medical thing as a form of punishment with him. This is what they do. There are other prisoners who probably could be healed or diagnosed with something at an early stage and because of their political affiliation or the politics in prison they won’t be seen.” LS, a 63-‐year-‐old man who has served 34 years in state prison, has seen chronically ill prisoners die: “Everyone that I’ve known here that contracted a serious disease such as cancer, just about all of them have died. I don’t know anyone here that survived cancer and has been here over the years. I know that’s not consistent with the care people get in society.” GU, a 69-‐year-‐old man who spent 41 years in state prison, also saw prisoners die: 6 “I’ve actually seen a man have a heart attack, laid on the floor; the corrections officer blew the whistle. They call it a medical emergency code 22. They came up to the unit and watched him and said they couldn’t do anything for him until medical staff came. Medical staff came twenty minutes after they came in the room. This man was in shock. He died. I watched him lie on the floor and die. That’s how poor the medical treatment is in the prison. […] I had a heart attack at 37 years old. I laid in the yard 45 minutes to an hour before they took me out of the yard. […] They then had to get approval for me to be taken from the prison to the hospital because I was in a close custody unit. I wound up not getting to the hospital until two hours later. I think had I not been exercising and eating a good diet I would have died.” Lack of adequate diet and exercise ML, a 42-‐year-‐old man who served more than a decade in state prisons, observed how poor diet contributes to poor health in aging prisoners: “Most people I knew as they aged in prison developed some type of ailment whether it was kidney failure, high cholesterol, high sugar because the food they serve is the worst of the worst. You can’t even identify it. A long-‐term diet of that is not good. So not only are you doing time, you are also going to have medical expenses. That just compounds things because you are not even going to get adequate medical services. […] In prison you deteriorate because you get inadequate medical assistance and at the same time you’re eating a diet that’s unhealthy. Even if you go to commissary, the only type products they offer in commissary are potato chips, snacks, soups that are high in sodium. There are no alternatives to an unhealthy diet. You are aging in prison, you’re not getting a proper diet, and you don’t get medical assistance so the combination of those things leads to the deterioration.” GU, a 69-‐year-‐old man who spent 41 years in state prison, described poor diet: “There are not very many healthy options in terms of diet in prison. The diet consists of basically sugar and starch. The meat products are of the lowest quality. The diet is very deficient of all the daily requirements a person would need for a healthy aging process. They are basically starving people nutritionally. It’s a form of genocide the way that they feed prisoners.” MU, a 54-‐year-‐old woman who spent ten years in state prisons, described lack of exercise: “When you are incarcerated you have one hour of rec and if you are in administrative segregation you probably have none.” RC, a 57-‐year-‐old woman who served four years in prison, described how prison officials have limited prisoners’ movement: “You can only go out for an hour a day. They don't even go out anymore to walk over to the mess hall. They bring the food to eat on the tier. Wherever you live that is where you eat. The only time you may go out is if you have classes. You can go to class and come back or whatever. Or the groups, whatever the groups are that may be offered now. They can go to those and come back. That's basically it.” 7 Lack of appropriate care for mental disability and disease GU, a 69-‐year-‐old man who spent 41 years in state prison, described an over-‐reliance on psychotropic drugs and long periods of confinement of people with mental illness: “The drugs will make you docile and then they put you in a closed confinement unit. They may leave you in the closed confinement unit for up to 25 years. I’ve seen it done in so many instances. […] Not only do you have elderly people with mental health concerns but you also have the young kids who come in now who are on these crazy types of drugs. In a general population of 1,600 people I would say 800 of them are on some form of psychotropic drugs. It’s a huge problem.” LS, a 63-‐year-‐old man, recalled: “They really don’t care for people with a mental illness. A lot of people in this environment mentally deteriorate. […] They don’t do anything for mental health in this place other than giving people medication … but there is very little therapy that people get that can be conducive to your well-‐being.” MU, a 54-‐year-‐old woman who spent 10 years in prison, described neglect of the mentally disabled or diseased: “I would see mentally ill patients sitting in their feces and throwing their food around. Sleeping in slop and that’s a form of illness. […] The way they treat mentally ill and people who are ill in general whether they are elderly or young is an abomination.” OL, a 71-‐year-‐old man who has served 28 years in state prison, described neglect of the mentally disabled or diseased: “The medical unit in prison is horrible. A guy might go down for medical care with dementia and they’d say there’s nothing we can do. With Alzheimer’s they would just put you in a cell and forget about you. In South Woods, we call it the death camp, because that’s where they send you to die, because they supposedly have the facilities to accommodate them but they just end up throwing you in a cell to waste away.” Lack of special provisions for elderly prisoners MU, a 54-‐year-‐old woman who spent 10 years in prison, said the prison officials treated the elderly prisoners the same as the others: “They treat the elderly like any other inmate. The idea of any special treatment for the elderly is out the door. Prison is prison. How they run the prison is inhumane, the same for everyone. It means you are faced with unprofessional guards. The word elderly is out of their vocabulary. You are a prisoner, plain and simple. They treat you like any other inmate.” RC, a 57-‐year-‐old woman who served four years, added: 8 “Mostly what I saw were women who came in aged. They came in wheelchairs. They were expected to do everything as we were doing. They didn't get any special help or consideration, nothing. If they had to go to medical one of the girls from on the tier would push them over. They had no one to help them or special accommodations.” MLR, a 42-‐year-‐old man who spent more than 10 years in various prisons, described how aging prisoners face difficulties with bunk beds: “No matter how old you are they’ll make you get up on the top bunk. You can have an obvious back injury and they will basically make you jump through hoops to get any consideration. You basically have to have recent back surgery and be damaged goods just to get approval for a bottom bunk. A guy sixty or seventy years old has to jump up and down off the top bunk with a mattress being too small.” GU, a 69-‐year-‐old man who spent 41 years in prison, also saw a pressing need for special accommodations: “The elderly prisoners are usually thrown in with the younger prisoners in double lock situations. The conditions for most older men are terrible because they live in the cells with these young kids. And these young kids are so disrespectful to these older men. Many of them suffer from mental illness if not physical sickness. […] Clearly there should be special housing for older prisoners. They need special medical care, they need special exercises, and they need counseling—all of things that are not provided in the general population for that age level. Sanitary conditions are horrendous because most older men can’t properly clean themselves. They don’t care; they just put them in a cell with another person.” JS, a 60-‐year-‐old man who served 30 years in Northern State prison, expressed the same view: “There should be a special area for older prisoners. There should be an area where they can confide with each other about health issues and work amongst each other. When you get older your movement slows down. In the population younger prisoners think older prisoners slow things down at work.” Impact of poor conditions and long sentences LS, a 63-‐year-‐old man who has served 34 years of his sentence, currently in Trenton State prison, described the impact of long sentences: “They have some astronomical sentences in these prisons. If you gave a 20-‐year-‐old a sentence of 60 or 70 years you’re telling them that they are going to die in there. […] A lot them didn’t realize they would be here that long. Sometimes it takes them a long time to realize they have a death sentence if they don’t get their sentence reduced or their convictions reversed.” He also observed how poor conditions cause prisoners to age faster: “I started seeing people being affected medically usually around their mid-‐30s in here. Because first the lack of mobility and the lack of nutritious diet. They buy the lowest cost food products they can find. So lack of nutritious diet and lack of movement is detrimental to everybody young or old. You see the effects 9 of it on men with rampant high blood pressure, heart disease and other diseases of obesity and even cancer.” GU, a 69-‐year-‐old man who spent 41 years in prison, described the psychological impact: “As you get older in prison you may no longer have the support of people who were there when you first came to prison. People and family begin to die. You don’t know how to develop resources to sustain yourself so your spirit begins to dwindle. Your physical health begins to dwindle. I’ve seen brothers in lockups who never come out of their cells. They never come out to the yard to exercise. They never do anything that is constructive or productive for their minds, bodies or their spirit.” SA, a 79-‐year-‐old man who has spent 43 years in prison, contracted tuberculosis from poor conditions: “I was locked down in one of the oldest parts of the prison that was infested with rats and tuberculosis bacteria in the walls, floors, cracks and crevices. Around age 40 or so, I began to suffer lower back pains sometimes so severe that the only remedy was ten straight days of bed rest. […] I was transferred into the federal system’s highest security prison and my entrance physical exam showed that I was infected with tuberculosis.” LC, a 55-‐year-‐old woman who spent five years in jails and prisons, also described the social/family impact: “Most women who spend decades in prison have no family left, no knowledge of the current outside world. We spend decades being told not only how to behave, but when to wake, sleep, eat, move, where to walk, and how and whom to talk with. To then expect someone at 70 to successfully transition back into society in a recipe for disaster. They have no experience left in basic decision making, and no guidance either before or after they are released.” 10 Preliminary recommendations for New Jersey12 Based on the testimonies in this report, we recommend that New Jersey develop and support laws and policies that enable the safe care, custody, and treatment of older prisoners, and facilitate the release of older prisoners who have completed the mandatory/punitive part of their sentences. These recommendations are based on the testimonies of this report and are modeled after recommendations made in the 2015 report, “Aging in Prison” from the Center for Justice at Columbia University. Specifically, we recommend the following: Sentencing • Amend extended sentencing laws to require the presumptive (i.e., presumed but rebuttable) parole of elderly prisoners. During incarceration • Enact a Bill of Rights specifically for elderly prisoners that incorporates standards for appropriate conditions of confinement, health care, diet, hygiene, recreation, socialization and family contacts. • Prohibit the solitary confinement of elderly prisoners. • Adopt comprehensive geriatric assessment tools. • Give greater weight to age and disability in classification rules, so that elderly prisoners are placed in prison facilities, units and single or double cells that are safe and appropriate to their condition. • Designate specific facilities and programs that can accommodate older prisoners with special needs. • Provide comprehensive training to prison staff on geriatric care and treatment. For release • Establish broader criteria for medical release, medical transfer, and medical parole that authorize these changes in status on the basis of mental as well as physical conditions. • Establish a specific presumption for the parole release of elderly prisoners, as soon as they have served the punitive part of their sentences. (See, e.g., the New York Safe and Fair Evaluation (SAFE) Parole Act pending (S01728/A02930), which bars parole denial on the grounds of the “nature of the original crime,” after the minimum sentence has been completed.) • Promulgate parole standards that properly balance risk factors in making parole release and "future eligibility term" (FET) determinations, by ensuring that age, low recidivism rates for older prisoners, and the length of time since the underlying offense are explicitly considered; ensure that fixed factors, such as the underlying offense, are not given undue or presumptive weight in the face of the dynamic factors of institutional history; ensure reasonable time frames for prisoners to make necessary changes in factors affecting risk. 11 • Promulgate guidelines for reentry plans for older prisoners that require the involvement of the prisoner in developing the plan, and include primary community support family and others in planning, with the prisoner's consent. • Provide referrals to appropriate community-‐based service providers, to ensure safe transitions and continuity of care. Oversight • Require that prison systems, in coordination with other human service public agencies, meet the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. • Establish a statewide office, independent of the Department of Corrections, to develop and monitor prison standards. 12 Acknowledgements The AFSC Prison Watch Program and its director, Bonnie Kerness, cannot express enough gratitude to everyone for their constant dedication and commitment over the process of this project. AFSC’s Prison Watch Program has always been a team effort including volunteers, students and activists on both sides of the prison walls. To those Prison Watch “staff” who were involved, thank you, including AFSC volunteer MaryAnn Cool and AFSC interns Kayla Stepinac, Rachel Frome and Kelsey Wimmershoff. The patience, research, writing and guidance of Jehanne Henry was loving and invaluable. Without the wisdom and mentorship of Jean Ross, this document would not have flourished. A special thank you for the encouragement of Tina Maschi of Fordham, School of Social Service, and Laura Whitehorn and Mujahid Farid of the New York Chapter of Release Aging People in Prison Campaign. Finally, we are most grateful to the elderly prisoners whose voices are suppressed every day and who refuse to be silent. Without their courageous voices and insistence that we share them, we on the outside would know nothing. AFSC Prison Watch The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) is a Quaker organization that includes people of various faiths who are committed to social justice, peace and humanitarian service. Prison Watch is a healing justice program that challenges the effectiveness of many of the conditions of confinement in the U.S. prison system. Prisoners and their families inform our efforts, as we work with policymakers, coalitions, other advocates and the legal community to change the paradigms of punishment to one of healing and transformation that seeks to restore wholeness to individuals and communities. We advocate for alternatives to incarceration, better mechanisms for reintegration after prison, and more humane conditions of confinement. We offer educational opportunities for young people, including academic internships and advocacy training. We reach thousands of individuals each year through presentations to faith communities, universities, and others. We also provide informational resources on topics such as surviving solitary confinement, sentence planning, and parole readiness to those incarcerated, their families, and other advocates. Prison Watch Program 89 Market Street, 6th Floor Newark, NJ 07104 Phone: 973-‐643-‐3192 Email: bkerness@afsc.org 13 End notes 1 See Human Rights Watch, “Old Behind Bars: The Aging Prison Population in the United States,” January 2012, at https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/01/27/old-‐behind-‐bars/aging-‐prison-‐population-‐united-‐states 2 New Jersey Department of Corrections, http://www.state.nj.us/corrections/pages/offender_stats.html 3 See N.J.S. 2C: 43-‐7.2. 4 See e.g. http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2014/06/04/maxout_report.pdf, People who complete their sentences leave prison without any authority for supervision. 5 Human Rights Watch, ibid. 6 See JOANN B. MORTON, U.S. DEP'T OF JUSTICE, AN ADMINISTRATIVE OVERVIEW OF THE OLDER INMATE 1, 4 (1992); Herbert J. Hoelter & Barry Holman, National Center on Institutions and Alternatives, Alexandria, VA, IMPRISONING ELDERLY OFFENDERS: MEDICAL CARE AND PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENTS ARE OF SPECIAL CONCERN (Dec. 1998) note 1, at 4. While age fifty seems closer to middle age than to elderly, the socioeconomic status, lack of access to medical care, and lifestyle of older criminals may create a ten year differential between the health of inmates in the Bureau of Prisons and the general population. Id.; Joanne O'Bryant, 7 Vera Institute of Justice, “It’s About Time: Aging Prisoners, Increasing Costs, and Geriatric Release,” April 2010, at http://archive.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/Its-‐about-‐time-‐aging-‐prisoners-‐increasing-‐ costs-‐and-‐geriatric-‐release.pdf 8 Matt Friedman, “More inmates would be eligible for medical parole under NJ legislation,” June 18, 2015, NJ Advance Media for NJ.com 9 Human Rights Watch, ibid, p. 72 10 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), arts. 7 and 10; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), art. 12; Convention Against Torture, art. 16; Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 11 Human Rights Watch, ibid. pp. 43-‐71 12 Center for Justice at Columbia University, “Aging in Prison: Reducing Elder Incarceration and Promoting Public Safety,” November 2015, pp XXVIII-‐XIX. 14 Suggested Reading Tina Maschi, PhD,* Deborah Viola, PhD, and Fei Sun, PhD. (2012). “The High Cost of the International Aging Prisoner Crisis: Well-‐Being as the Common Denominator for Action.” The Gerontologist Advance Access. Tina Maschi, George Leibowitz,, and Joanne Rees3 & Lauren Pappacena. (2016). “Analysis of US Compassionate and Geriatric Release Laws: Applying a Human Rights Framework to Global Prison Health.” Journal for Human Rights Social Work. Tina Maschi, Lindsay Koskinen. (2015). “Co-‐Constructing Community: A Conceptual Map for Reuniting Aging People in Prison with Their Families and Communities.” Traumatology. Tina Maschi, Lindsay Koskinen, Deborah Viola. (2015). “Trauma, Stress, and Coping Among Older Adults in Prison: Towards a Human Rights and Intergenerational Family Justice Action Agenda.” Special Issue on Trauma, Aging, and Well-‐Being: American Psychological Association. 15