Naacp Legal Defense and Education Fund Free the Vote Felon Disenfranchisement 2009

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

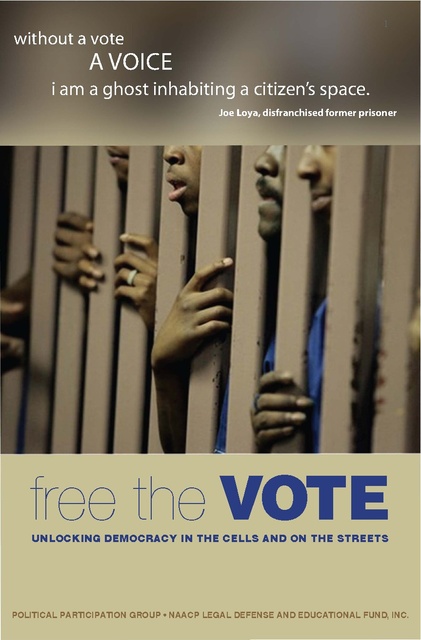

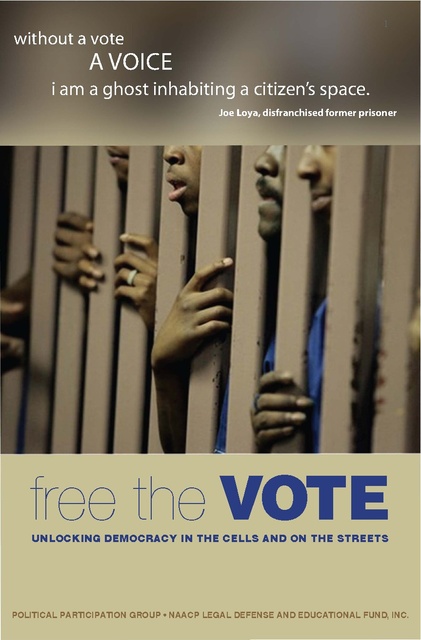

1 without a vote a voice i am a ghost inhabiting a citizen’s space. Joe Loya, disfranchised former prisoner free the VOTE UNLOCKING DEMOCRACY IN THE CELLS AND ON THE STREETS POLITICAL PARTICIPATION GROUP • NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. 1 NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. John Payton President and Director-Counsel National Headquarters 99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600 New York, NY 10013 212.965.2200 800.221.7822 Fax 212.226.7592 Ryan P. Haygood Co-Director, Political Participation Group Jenigh Garrett Assistant Counsel Dale Ho Assistant Counsel Washington, DC Office 1444 Eye Street NW, 10th Floor Washington, DC 20105 202.682.1300 Fax 202.682.1312 Kristen Clarke Co-Director, Political Participation Group For more information, visit us at www.naacpldf.org LDF’s POLITICAL PARTICIPATION GROUP The Political Participation Group’s mission is to use legal, legislative, public education, and advocacy strategies to promote the full, equal, and active participation of African Americans in America’s democracy. 1 FREE THE VOTE Unlocking Democracy in the Cells and on the Streets The Next Phase of the Voting Rights Movement: Freeing the Vote for People with Felony Convictions Securing the right to vote for the disfranchised—persons who have lost their voting rights as a result of a felony conviction—is widely recognized as the next phase of the voting rights movement. Nationwide, more than 5.3 million Americans who have been convicted of a felony are denied access to the one fundamental right that is the foundation of all other rights. Only Maine and Vermont do not restrict voting on the basis of a felony conviction, and allow inmates to vote from prison by absentee ballot. Nearly 2 million, or 38%, of the disfranchised are African Americans. A staggering 13% of all African-American men in this country—and in some states up to one-third of the entire African-American male population—are denied the right to vote. Given current rates of incarceration, an astonishing one in three of the next generation of Black men will be disfranchised at some point during their lifetime. 2 Felon disfranchisement laws are a modern version of historic voting barriers like Black Codes, Jim Crow laws, literacy tests, and poll taxes. Electoral Exclusion: The Past and the Present The racial disparities caused by felon disfranchisement laws are not a coincidence. Many felon disfranchisement laws were passed in the years following the Civil War for the distinct purpose of discriminating against newly-freed African Americans. Indeed, many state legislatures tailored their felon disfranchisement laws to require the loss of voting rights only for those offenses thought to be committed most frequently by Blacks. For example, guided by the belief that Blacks engaged in crime were more likely to commit less serious property offenses than the more “robust” crimes committed by whites, the 1890 Mississippi constitutional convention required disfranchisement for such crimes as theft or burglary, but not for robbery or murder. Through the convoluted reasoning of this law, one would be disfranchised for stealing a chicken, but not for killing the chicken’s owner. Many other states, from New York to Alabama, have also historically utilized felon disfranchisement laws to prevent Blacks and other racial minorities from voting. 3 Modern Day Impact on Communities of Color As intended, felon disfranchisement statutes have weakened the voting power of Black and Latino communities. This is largely the result of the disproportionate enforcement of the “war on drugs” in Black and Latino communities, which has drastically increased the class of persons subject to disfranchisement. Today, with 2.3 million Americans incarcerated, more than 1 million of whom are African Americans, the effects of our nation’s reliance on mass incarceration in the “war on drugs” era is more profound than ever. Nowhere are the effects of felon disfranchisement more prominent than in the Black community, where more than 1.5 million Black males, or 13% of the adult Black population, are disfranchised—a rate seven times the national average. The impact on Black voting strength at the state level is devastating. In Alabama, for example, one in three Black men have been disqualified from voting as a result of a felony conviction. In Washington State, an incredible 24% of Black men, and 15% of the entire Black population, are denied their voting rights. In New York, though Blacks and Latinos collectively comprise only 30% of the State’s overall population, they represent an astonishing 87% of those denied the right to vote because of a felony conviction. Nearly 2 million, or 38%, of the disfranchised are African Americans. A staggering 13% of all African-American men in this country are disfranchised. In some states up to one-third of the entire African-American male population is denied the right to vote. Culture of Political Nonparticipation Felon disfranchisement laws discourage voters and future voters from exercising the learned behavior of voting. In doing so, these laws create a culture of political nonparticipation that discourages civic engagement and marginalizes the voices of community members who remain engaged, but who are deprived of the collective power of the votes of disfranchised relatives and neighbors. 4 Voices of Entire Communities Weakened Felon disfranchisement affects more than individual voters themselves—it diminishes the voting strength of entire minority communities, which are too often already plagued with concentrated poverty, substandard housing, limited access to healthcare services, and failing public schools. As a result, people in these communities have even less of an opportunity to effect much-needed positive change through the political process. Prisoners of the Census To make matters worse, the Census Bureau counts incarcerated people as residents of the prisons in which they are housed, which are often rural communities, rather than in their permanent, pre-incarceration communities, which are often in the inner-cities. Because racial minorities make up a substantially disproportionate number of sentenced prisoners, this practice artificially inflates population numbers in the overwhelmingly white towns, villages and counties that house prisons, resulting in greater political influence and increased economic resources to rural areas and a loss of resources to the inner-city communities from which minority prisoners usually belong. Moreover, the Census Bureau’s current method of counting prisoners violates the basic principle of “one person, one vote.” For example, in the city of Anamosa, Iowa, a councilman from a prison community was elected to office from a ward which, according to the Census, had almost 1,400 residents — about the same as the other three wards in town. But 1,300 of these “residents” were actually prisoners in the Anamosa State Penitentiary. Once those prisoners were subtracted, the “ward” had fewer than 60 actual residents. New Frontiers for the Expansion of Voting Rights 5 Today, there are new frontiers for the expansion of voting rights, and old battles that remain unfinished. Regrettably, more than a century after emancipation, and 45 years after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, increasing numbers of Blacks and Latinos nationwide are actually losing their right to vote each day, rather than experiencing greater access to political participation. Fortunately, new efforts to reform felon disfranchisement policies suggest that many lawmakers are beginning to understand that felon disfranchisement is not only discriminatory in its application, but also undermines the most fundamental aspect of American citizenship: the right to participate in the political process. LDF is the leading voice in engaging the public and challenging discriminatory felon disfranchisement laws in state and federal courts across the nation, litigating cases in New York (Hayden v. Paterson), Washington State (Farrakhan v. Gregoire) and Alabama (Gooden v. Worley and Glasgow v. Allen). Through these efforts, we aim to erase these racially discriminatory laws from the books. But we need your help. What Can You Do? • Educate Yourself: Find out what the felon disfranchisement policy is in your state, and what efforts are underway to change that policy. • Educate Others: Tell others in your community about the discriminatory impact of these laws. Let them know how imperative each and every vote is to effectuating change in your community, and ultimately, in your city, state and country. • Volunteer: If you live in a state where voting rights for people with felony convictions can be restored, there may be local or community organizations that can help guide them through the process. There may also be community organizations in your area that advocate for changes to felon disfranchisement laws. Sign up to volunteer for one of these organizations. • Take Political Action: Contact your state and federal representatives and let them know that you believe these laws are anti-democratic, discriminatory, and should be swept into the dustbin of history, along with Jim Crow laws, literacy tests, and poll taxes. Together, we can empower ourselves, enhance our collective voting strength, and improve the conditions of our communities, by freeing the vote for people with felony convictions. 6 Civil Rights Marchers Alabama, 1965 =___ ==~======I====:=~\ LDF Attorneys at the Supreme Court, 2009