PEW - The Impact of Parole in New Jersey, 2013

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.

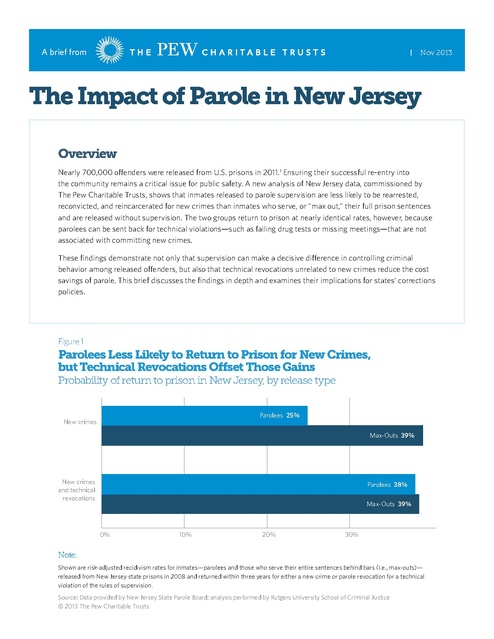

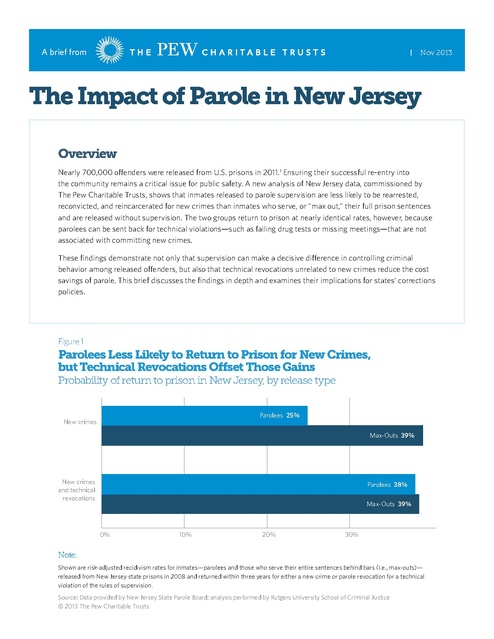

A brief from Nov 2013 The Impact of Parole in New Jersey Overview Nearly 700,000 offenders were released from U.S. prisons in 2011.1 Ensuring their successful re-entry into the community remains a critical issue for public safety. A new analysis of New Jersey data, commissioned by The Pew Charitable Trusts, shows that inmates released to parole supervision are less likely to be rearrested, reconvicted, and reincarcerated for new crimes than inmates who serve, or “max out,” their full prison sentences and are released without supervision. The two groups return to prison at nearly identical rates, however, because parolees can be sent back for technical violations—such as failing drug tests or missing meetings—that are not associated with committing new crimes. These findings demonstrate not only that supervision can make a decisive difference in controlling criminal behavior among released offenders, but also that technical revocations unrelated to new crimes reduce the cost savings of parole. This brief discusses the findings in depth and examines their implications for states’ corrections policies. Figure 1 Parolees Less Likely to Return to Prison for New Crimes, but Technical Revocations Offset Those Gains Probability of return to prison in New Jersey, by release type Parolees 25% New crimes Max-Outs 39% New crimes and technical revocations Parolees 38% Max-Outs 39% 0% 10% 20% 30% Note: Shown are risk-adjusted recidivism rates for inmates—parolees and those who serve their entire sentences behind bars (i.e., max-outs)— released from New Jersey state prisons in 2008 and returned within three years for either a new crime or parole revocation for a technical violation of the rules of supervision. Source: Data provided by New Jersey State Parole Board; analysis performed by Rutgers University School of Criminal Justice © 2013 The Pew Charitable Trusts Background New Jersey releases more than 10,000 inmates from its state correctional facilities each year.2 About 60 percent of them are released to parole supervision before the end of their prison sentences. In most cases, the New Jersey State Parole Board makes decisions about who is granted such conditional release and the specific requirements that parolees must satisfy to avoid revocation to prison. These typically include reporting to a parole officer and abstaining from use of illicit drugs. The board has authority to rescind parole and send offenders back to prison if conditions are violated or new crimes are committed. The other 40 percent of offenders released from state custody are max-outs—inmates who complete their prison sentences and are not subject to supervision upon returning to the community. This proportion of inmates who serve their full sentence has increased in recent years, rising from 35 percent in 2004. Overall, recidivism rates are falling in New Jersey. Among inmates released in 2008, within three years 56 percent were rearrested, 44 percent were reconvicted, and 30 percent were reincarcerated, compared with 60 percent, 50 percent, and 38 percent, respectively, in 2004.3 Recidivism is the act of re-engaging in criminal behavior after having been punished. Prison recidivism, the focus of this study, refers to people who were released from prison and rearrested, reconvicted, or reincarcerated for new crimes or returned to prison for either new crimes or technical violations within a given time period. Key findings To better understand the impact of parole supervision on offender outcomes, Pew commissioned the Rutgers University School of Criminal Justice to compare the performance of parolees and max-outs. One of the first studies of its kind, the research analyzes three-year outcomes using multiple measures of recidivism and adjusts those rates based on offenders’ risk levels—the critical step in making legitimate comparisons between the two groups. Supervised parolees perform better than max-outs Overall, parolees engaged in new criminal behavior at a significantly lower rate than max-outs. Specifically: •• Parolees were less likely than max-outs to be rearrested within three years of release in 2008 (51 percent versus 65 percent) and less likely to be reconvicted of a new crime (38 percent versus 55 percent). •• About 25 percent of parolees released in 2008 committed new crimes and returned to prison within three years, compared with 41 percent of offenders who maxed out their sentences, were released without supervision, and subsequently committed new crimes. •• As a group, max-outs tend to be higher-risk offenders than parolees, but, even when controlling for key risk factors such as age, time served, current offense, and criminal history, parolees are still 36 percent less likely to return to prison for new crimes within three years of release. Thus, accounting for the risk profile of the two offender groups diminishes but does not eliminate the public safety benefits of parole supervision. The risk-adjusted probability of being returned to prison for a new crime is 25 percent for parolees and 39 percent for max-outs. 2 Nearly half of rearrests within three years of an inmate’s release from prison occur after parole supervision has ended. The finding that parolees have a lower likelihood of reoffending than max-outs of similar risk levels is not the only result indicating that supervision is playing a pivotal role in deterring new criminal behavior. Also notable is that many rearrests occur after a parolee has been discharged from supervision. Among parolees rearrested within three years after a 2008 release from prison, 48 percent were no longer under supervision. Of these, 8 out of 10 had successfully completed parole, meaning they not only had been discharged but also were not revoked at any time while under supervision. Technical violations offset prison savings The cost of parole supervision generally is one-tenth that of incarceration.4 This means offenders who serve shorter prison terms followed by parole supervision cost less than offenders who serve their full sentences behind bars. But unlike max-outs, parolees can be sent back to prison for violating the rules governing their release, such as missing appointments and failing drug tests. Large numbers of parolees are being returned to prison for these violations, substantially reducing the cost savings. Parole revocations for technical violations in New Jersey declined 28 percent among inmates released in 2008 compared with those released in 2004, reflecting a concerted effort by the parole board to use sanctions other than revocation to hold violators accountable. Still, more than 1 in 5 inmates released to parole supervision in 2008 were returned to prison for violating conditions set by the board. Records show that none of these revocations included an arrest, meaning each was judged to be a rules violation and did not result from commission of a new crime. These technical revocations, however justified, offset the cost benefit of parolees’ otherwise lower rearrest and reconviction rates compared with max-outs. Indeed, after controlling for individual risk factors, parolees are just as likely—38 percent—to be returned to prison within three years of release, either for a new crime or a revocation, as offenders released without supervision (39 percent). Policy implications Analysis of the New Jersey experience sheds new light on the efficacy of parole supervision to protect the public while controlling the cost of corrections. By statistically comparing offenders who maxed out their prison terms with similar offenders who were released to parole supervision, the analysis is able to compare the impact of the two policy options. Because parolees are less likely to be rearrested and reincarcerated than those who maxed out, states could get better public safety outcomes at a lower cost if all inmates were released to supervision rather than remaining behind bars until the expiration of their sentences. Several states have recently enacted policies to ensure that every inmate receives a period of post-release supervision. In 2011, Kentucky enacted Mandatory Reentry Supervision, or MRS, as part of its omnibus Public Safety and Offender Accountability Act (H.B. 463). MRS policy requires that inmates be released to mandatory post-release supervision no less than six months before the expiration of their sentences if they have not been granted discretionary parole before that time. 3 Ensuring that inmates receive a period of post-release supervision is a critical first step, but to provide the greatest benefit, parole must also be done well. Although further research is necessary to understand which elements of parole supervision in New Jersey are most effective at deterring criminal behavior, states across the country are adopting policies and practices to provide a greater public safety return on corrections spending. Chief among these strategies are focusing supervision resources on high-risk offenders by allowing parolees to earn their way off supervision and concentrating prison space on violent, serious, and chronic offenders by limiting parole revocations for technical violations. Several states allow offenders to earn their way off supervision if they comply with the rules governing their release. These “earned discharge” policies can be powerful incentives for offenders to abstain from criminal behavior, and they allow parole agencies to tailor supervision to individual offenders. Arkansas’s Public Safety Improvement Act of 2011, for example, grants its community corrections agency the authority to discharge offenders at one-half of their community supervision terms if they have complied with conditions and committed no new crimes. Many states also have adopted policies to address noncompliance with sanctions short of a costly return to prison. Examples include authorizing the use of short jail stays for violations, establishing a system of graduated sanctions, and limiting the amount of time that an offender can be returned to prison for a technical revocation. Case in point: As part of its 2011 Justice Reinvestment Act, North Carolina instituted a 90-day cap on revocation time for technical violations of post-release supervision. States have enacted several policies to strengthen community supervision, with the twin goals of protecting public safety and reducing corrections costs: Mandatory re-entry supervision: Kansas, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, West Virginia. Earned discharge: Arkansas, Delaware, Kansas, Kentucky, Missouri, New Hampshire, South Carolina, South Dakota. Short jail sanctions: Arkansas, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, New Hampshire, North Carolina, South Carolina, West Virginia. Graduated sanctions: Arkansas, Delaware, Georgia, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, West Virginia. Revocation caps: Alabama, Hawaii, Kansas, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania. 4 Conclusion This research provides new evidence that inmates released to parole supervision are less likely to reoffend than inmates who serve their full sentences. It also highlights a key challenge: For parole supervision to be a costeffective alternative to keeping offenders behind bars for their entire sentences, policymakers and paroling authorities need to develop additional strategies that hold offenders accountable for violations without returning them to expensive prison cells. In the past several years, states around the country have embraced a variety of reforms to their parole policies. Among these are ensuring that every inmate receives a period of post-release supervision; focusing supervision resources on high-risk offenders; and concentrating prison space on violent, serious, and chronic offenders by limiting parole revocations for technical violations. States that continue to adopt and evaluate the impact of evidence-based policies and practices will be rewarded with safer communities and lower taxpayer costs. Endnotes 1 E. Ann Carson and William J. Sabol, Prisoners in 2011, U.S. Department of Justice Bulletin (December 2012), http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/ content/pub/pdf/p11.pdf. 2 This study includes people who were released from New Jersey state prisons. State prisoners are sentenced on indictable offenses to terms of 365 days or more. The study does not include inmates charged with disorderly-person offenses or those sentenced to terms of 364 days or less. These inmates serve their terms in county jails rather than state prisons. 3 Unless otherwise cited, data contained in this report were provided by the New Jersey State Parole Board and analyses were performed by Mike Ostermann, Rutgers University School of Criminal Justice. 4 Pew Center on the States, One in 31: The Long Reach of American Corrections (Washington, DC: The Pew Charitable Trusts, March 2009), 13. http://www.pewstates.org/uploadedFiles/PCS_Assets/2009/PSPP_1in31_report_FINAL_WEB_3-26-09.pdf. For further information, please visit: pewstates.org/publicsafety The Pew Charitable Trusts’ public safety performance project would like to thank Mike Ostermann of the Rutgers University School of Criminal Justice for this original research and acknowledge the contributions of Bill Burrell and Kristin Golden as external reviewers. Support for this brief was provided by the following project staff members: Karla Dhungana, Brian Elderbroom, Adam Gelb, Ryan King, Pam Lachman, and Christina Zurla. We also would like to thank Jenifer Warren and Jennifer Doctors for writing and editing. The Pew Charitable Trusts is driven by the power of knowledge to solve today’s most challenging problems. Pew applies a rigorous, analytical approach to improve public policy, inform the public, and stimulate civic life. 5