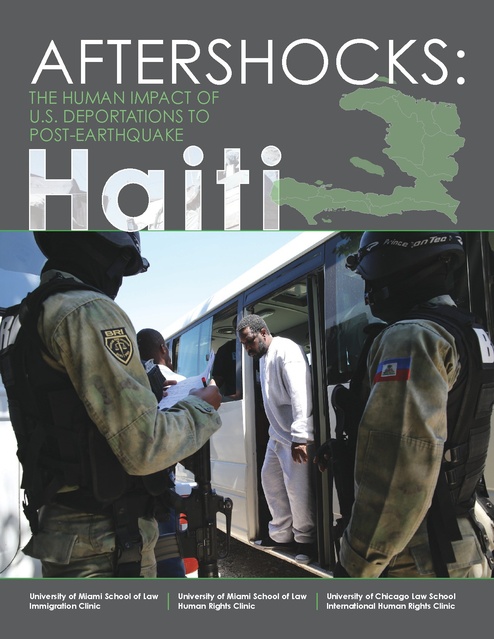

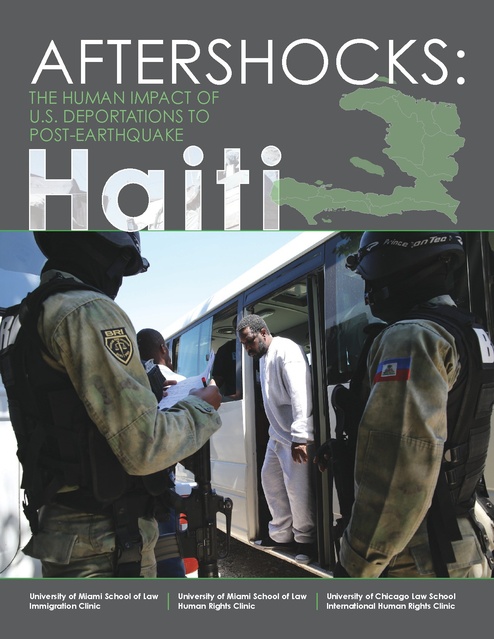

Aftershocks: Impact of U.S. Deportations to Haiti, U. Miami Immigration Clinic, 2015

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.