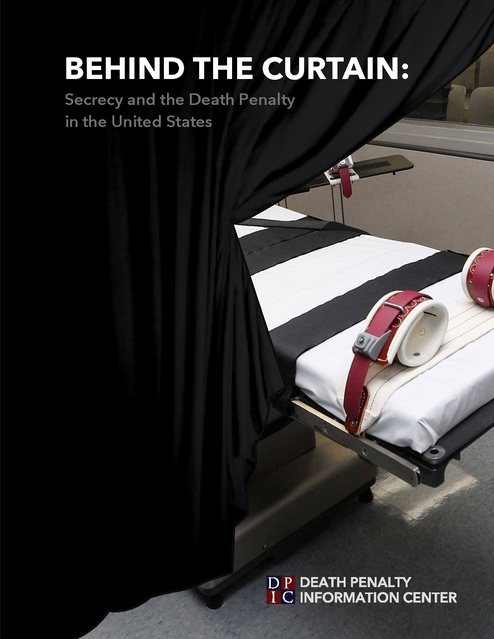

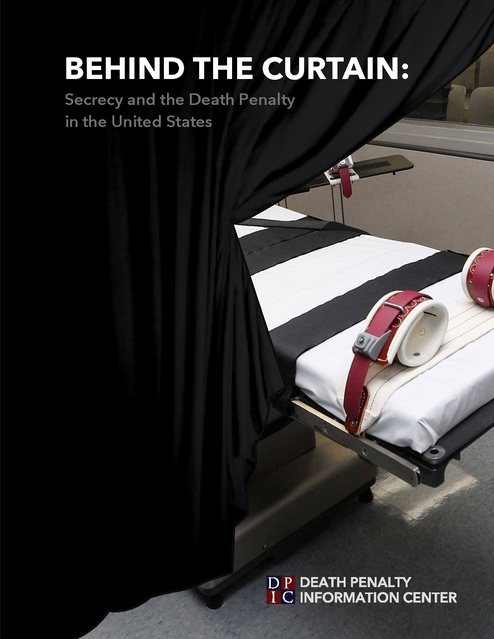

Death Penalty Information Center - Behind the Curtain - Secrecy and the Death Penalty, 2018

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.