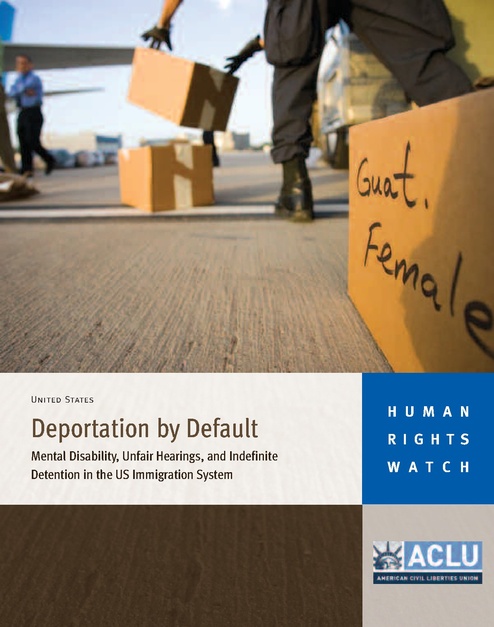

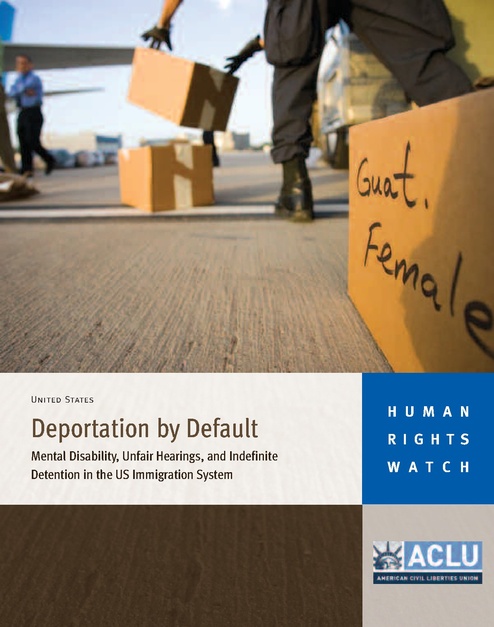

Deportation by Default - Mental Disability, Unfair Hearings, and Indefinite Detention in the U.S. Immigration System, HRW ACLU, 2010

Download original document:

Document text

Document text

This text is machine-read, and may contain errors. Check the original document to verify accuracy.